Chapter 2

The Philosophy of Existence

2.3 Quantisation of spacetime

2.3.2 Time

What is time? There is no clear, generally accepted and unambiguous definition of time. What we do know, is that time enables us to describe the order and sequence of events or developments, to quantify how long they last or intervals between them.

On this matter, the Philosophy of Existence states [1], page 87: „There is no past. There is no future. Everything is now!” The Creative Work (note: this refers to our entire world) endures in its motionlessness. The past and the future are simultaneous. Only we, our “I am” rove in the completed events and create the notion of time in our mind.“

According to the Philosophy of Existence, time can only be understood in relation to the observer and his connection to our world, which is otherwise a completely static object (!).

There is no time without an observer. In other words, time is just one way of looking at a finished product. Imagine a river on a map – we perceive it as solid, timeless, static object. But if we connect to it, become a drop of water within it, its motion makes us perceive its dynamic expression in time – to us, time then exists.

In our perception, time is inseparably connected to motion. Without motion we cannot perceive time (!). However, when we quantify time, it is always connected to some kind of periodic movement, oscillation (may it be oscillation of a pendulum clock or measurement of light beam reflections between two mirrors according to the special theory of relativity). And so it is understandable that time as such always and inevitably OSCILLATES in our perception.

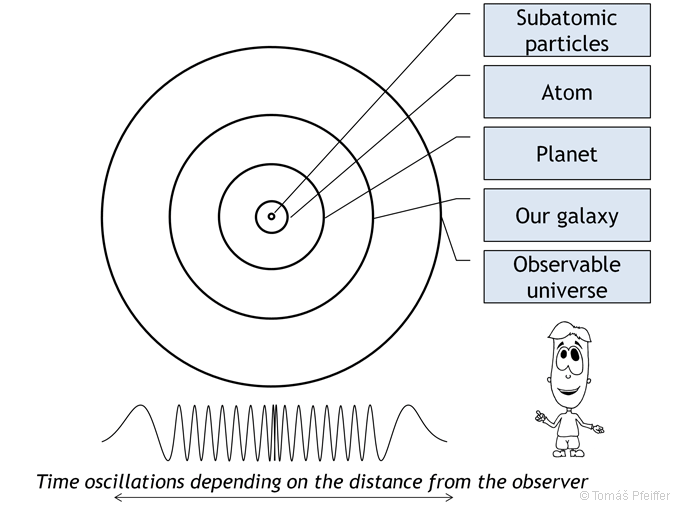

When observing objects (intervals) close to the observer, time seems to be a perfectly continuous and uniform continuum. The case is completely different at the horizon of cognition.

When we move into the micro world (observing smaller and smaller parts), the time we perceive accelerates alongside the growing frequency of the micro world’s vibrations (oscillations). They accelerate to such an extent that, as we draw close to the horizon of cognition, we are no longer able to register any motion (and thus lose the ability to quantify time). The perception of time disappears, blends and crumbles into a static set of possible states (of time quanta) that are perceived simultaneously. There is a border frequency beyond which we cannot perceive anything. This is why to us, time is a fractal property, just as everything else.

Science relates to this when speaking of Planck time [28]. In 1899, Max Planck defined a Planck second as the time it takes for a photon in a vacuum to travel 1 Planck length. According to our current knowledge, nothing can happen in less time than a Planck second, and this time interval is considered to be the basic time quantum. Planck time is approximately 5.39×10−44 s [29], whereas the shortest measured time interval is an attosecond (10−18 s) [30], which is approximately 1026 Planck seconds. This shows that, in relation to time scales, science also recognises the existence of the horizon of cognition.

Moving into the macro world (observing larger and larger objects), the time we perceive slows down alongside the decreasing frequency of the macro world’s vibrations (oscillations). It slows all the way to zero (similar to the horizon of black holes) or when travelling at relative velocities comparable to the speed of light (the special theory of relativity). Our perception of time thus disappears and we only perceive a single given state, one static quantum (of the whole universe) and, again, we lose any ability to measure or quantify it. The perception of additional time increments disappears, blends and crumbles into a static set of possible states (of time quanta) that are perceived simultaneously. It is not possible to quantify anything in a state of absolute rest (zero frequency).

The change in time perception when moving into the micro or macro world is illustrated in Fig. 2.4.

The illusion of time acceleration and deceleration is a manifestation of the horizon of cognition and of the fractal structure of our world that is direct consequence of the horizon of cognition.

Philosophically, time can be understood as oscillations between two poles. These oscillations enable us to perceive and observe sequences; they provide us with a causality scale. Nothing oscillates in the undivided state (point zero for time and space) – there is no causal perception of time. Time only came into being with the process of division, and nothing has been at rest in the universe ever since. At the same time, our ability to distinguish time and causality completely disappears at the limit or our observations, given by the horizon of cognition.

From another perspective (4D) time exists (as a consequence of division) in a static form and it is only a 3D observer that makes it dynamic. In other words, all possible changes of state also exist in their constant, unchanging and infinite form. It is just the 3D observer that brings due to his observing this static time to life, makes it localised, determines the dynamic a place of a specific time oscillation.